An Exploration of the Trust-Commitment Cultural Model and Its Role in the Success of Women Entrepreneurs

Abstract

Survey data analysis in three stages over a five year period is reported to explore the idea that successful women business owners develop and utilize a "culture of trust and commitment" in their firms and that this culture is a fundamental contributor to their high financial and organizational performance. Responses of more than 1,000 employees from 18 small businesses (14 owned by women, 4 by men) to the 95 questions of the Quality Leadership Survey (QLS) are given. The QLS in part directly assesses the broad concept of culture and the specific constructs of trust and commitment. Extensive statistical calculations are employed to examine the possibility that trust and commitment are closely linked and are the foundation of a distinct culture created and nurtured by outstanding women entrepreneurs. The authors believe the education and training on the subject of culture will be very helpful to current and future entrepreneurs.

An Exploration of the Trust-Commitment Cultural Model and Its Role in the Success of Women Entrepreneurs

For more than three decades, women have been making extraordinary strides in the U. S. entrepreneurial arena. From 1970 to 2000, the number of women small business owners went from a half million to more than nine million (Office of Advocacy, 2005). If such a pace continues, this group could expand to 12 million or more in this current decade. The authors of this paper seek to explore what they believe is a major reason for this growth--the culture that is created by these women in their businesses. Also examined here is the idea that future women business owners will benefit greatly from understanding the role of culture in their entrepreneurial success.

One of the authors in previous writings has suggested that successful women business owners have entrepreneurial and team oriented personalities, as well as a participative/consultative managerial approach which strongly aid them in their entrepreneurial efforts ( Davis , 2001; Davis , 2005a; Davis , 2005b; Davis & Hollingsworth, 2000). The authors in this paper propose another possible reason for the success of these women is their developing and employing a trust-commitment culture in their businesses, which leads to high employee and organizational performance over the long term. This essay explores this idea that outstanding women business owners in this country, for a number of reasons, create a particular cultural model or, "blueprint," that guides their businesses on a daily basis. These women exhibit an extraordinary level of trust and commitment for their employees which then is morphed into an unusually high level of trust and commitment by employees for the owners and their businesses.

This careful assessment of the kind of culture that is found with women entrepreneurs who stand at the top of the small business world proceeds in two phases. The first phase deals with a review of what has been published in terms of how trust and commitment have individually been studied and regarded in organizational functioning. This review suggests that these two concepts are linked closely together when considering the culture created in successful firms owned by women. The second phase of this paper reports on the in-depth analysis of the survey results of 18 small businesses (14 owned by highly successful women entrepreneurs and 4 owned by men). This analysis brings together, in practical and women entrepreneur developmental terms, what has been discussed in the first phase.

Trust and Commitment as Organizational Culture Concepts

The history of trust as a theoretical construct in organization development, business systems, counseling, and education/learning can be traced to the 1960s (Gibb, 1978). In recent years, there has been a considerable amount of interest shown here in the US and overseas in the concept of trust and its impact on organizational performance (Ciancutti & Steding, 2001; Costigan & Iter, 1998; Dietz, 2004; Dirks & Ferrin, 2000; Kramer & Tyler, 1996; Kramer, 1999; Lane & Bachmann, 2003; McCauley & Kuhnert, 1992; O'Brien, 2001; Ramo, 2004; Tyler, 2003). Dietz carefully defines five different categories of trust as it operates within an organization. Tyler argues trust is highly important, particularly to a modern organization which must manage its dynamics efficiently to ensure its survival and growth. Ciancutti and Steding (2001) write,

We are a society in search of trust. The less we find it, the more precious

it becomes. An organization where people earn one another's trust - and

one that commands trust from the public - has a competitive advantage.

It can draw the best people, inspire customer loyalty, reach out successfully

to new markets, and provide more innovative products and services. You

can intentionally create trust. You can drive a culture of earned trust that includes everyone and harvests opportunities to increase growth, produc- tivity, profits and job satisfaction with virtually no cost to you. (p. 11)

Dirks and Ferrin, in their 2000 meta-analysis of 47 studies on trust, concluded that trust in leadership has an important effect on employee job performance, organizational citizenship behaviors, intent to quit, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction.

It would appear that substantial time and attention has been paid in the last several years to the impact of trust on the organization. For those who would go further into the history of what has been done by researchers in the past two decades as it relates to business performance, McCauley and Kuhnert (1992) may serve as a valuable reference. These two writers conclude that the association between trust and performance has been expressed by most of the researchers they have reviewed.

In a similar vein, there has been in the past ten years considerable American and worldwide attention given to the subject of commitment and what it means to individual and organizational performance (Baron & Kreps, 1999; Becker, Billings, Eveleth, & Gilbert, 1996; Beyerlein, Freedman, McGee, & Moran, 2003; Brooks & Zeitz, 1999; Foote, Seipel, Johnson, & Duffy, 2005; Kim &Rowley, 2005; Meyer & Allen, 1997). Both the Becker, et al., and the Brooks and Zeitz articles track back to the 1970s the extensive research that has taken place on the subject of commitment.

From these many, the authors at this point would like to feature one longitudinal study done by the Stanford Graduate School of Business, as reported by Baron and Kreps (1999), in order to highlight and to underscore the role of commitment in the design, creation, and evolution of a small business's culture. The Stanford Project on Emerging Companies (SPEC) began in the 1990s and continues to this day.

In 1994, a group of researchers at the Stanford Graduate School of Business began studying 186 young high tech companies located in the Silicon Valley . Using interviews, surveys, and archival publications, their aim (then and to the present) has been to examine management's, especially the founder's and/or CEO's, thinking and actions on human resource practices, organization design, and business strategy. The team has been particularly interested in noting the evolution of this thinking and action taking, as well as looking at the impact of these early decisions on the firms' performance (Stanford Project on Emerging Companies, 2004).

One of the overall findings by this Stanford team that helps researchers involved with the study of small businesses dealt with the strategies of these firms. Five primary strategies were identified by the SPEC research team as being those used by their Silicon Valley companies: 1) Innovators - companies striving to create novel products for new undeveloped markets; 2) Enhancers - those striving to improve upon products for already developed markets; 3) Marketing - those whose core competency lies in the marketing, distribution, and selling of their products; 4) Technology/Marketing Hybrids - those who have significant innovator/enhancer characteristics and who have marketing prowess as well; and 5) Cost - those competing primarily by providing their product at a low cost.

A second important finding that pertains directly to the major interest of this paper, SPEC researchers narrowed to four the number of what they called "Pure Management/Employment Models or Blueprints" utilized by the companies studied:

1) Factory - companies who tend to simply see their employees as a cost of production, which should be minimized just like any other costs of production; 2) Commitment -

companies fostering a long-term friendly two way communication between employer and employee who emphasize training and development of employees seeking to retain employees for long durations; 3) Star - companies seeking to recruit the best and brightest talent in the industry; and 4) Engineering - companies seeking to organize workers into teams who can then be assigned to specialized tasks.

Twenty-nine of these Silicon Valley companies started their businesses with the Commitment model (with all the five strategies being employed among the 29) in the mid-1990s. As of the last report, 22 firms were still using this model (all strategies involved). The authors of this paper would like to suggest that this Commitment management or employment model found by SPEC is in theory and possibly in fact very much in keeping with the concept of a commitment culture, which values highly the training, development, and retention of its most important resource, its employees. Stanford's work on the SPEC, consequently, gives to those of us who are pursuing the clarification of the role and importance of culture inside small businesses encouragement to proceed to examine the theory that commitment is possibly a vital key.

As to the availability of past research that examines the trust and commitment constructs operating together in terms of a single culture, not much, if any, previous formal published research has occurred. One writer in the last few years (de Gilder, 2003) has investigated the perceptual differences in trust and commitment between two types of hotel workers. He found a "significant" correlation between the two as independent variables. Mentioned earlier was the work of Dirks and Ferrin (2000), who see the two as functioning together in a significant way. The two authors who come very close to the position of this paper are Ciancutti and Steding (2001), who, in their Built on Trust book, describe a culture of trust being founded on six principles, one of which is commitment. It might be worth bringing out at this juncture that this paper is exploring rather new ground by suggesting trust and commitment may be closely tied to one another in the creation and maintenance of a culture, which leads to the success of small businesses, especially those owned by successful women entrepreneurs. The logic being examined here is: "If employees have a high level of trust in the owner and the organization then a high level of commitment to the owner and organization will likely be an accompanying valuable outcome." The reverse logic of commitment creating trust does not seem as plausible. Inside this logic is the idea that the woman business owner gets the Trust/Commitment "ball" rolling. In any case, the information in the next section is presented in order to provide some statistical substantiation that trust and commitment are in a marriage that serves as a fundamental basis for the culture developed and nurtured by highly successful women business owners.

A Survey Study of Highly Successful Women Entrepreneurs

In 1998, one of the authors began a long term examination of highly successful women entrepreneurs. The extraordinary movement of women into the ranks of business owners over the three decade period beginning in 1970 was cause for a closer scrutiny of what had been taking place, particularly from the standpoint of what needed to be done for the training and development of this mushrooming group. This researcher began by a serious study of the personalities of 56 of the top 500 women business owners (based on sales revenue) as identified by Working Woman magazine. Several articles and a book, The Succeeding Personalities of Women Entrepreneurs ( Davis , 2001), resulted. His next phase of research was the study of 14 of these 56 women and their managerial style. A primary question he sought to answer was whether their managerial approach was possibly a cause of their success. This survey data gathering ended in 2000 with over 500 employees from these women's 14 businesses completing the Quality Leadership Survey (QLS), a 95 item standardized instrument which measures 32 factors of organizational functioning across five organizational levels. In addition to this data, an almost equal number of employees from four men-owned small to medium sized going business concerns had responded to the same survey during the mid 1990s. The survey results from these men-owned firms allowed a comparison to note any gender difference in managerial style.

What follows below reviews the three stages of survey data analysis which has taken place to get to the point now of examining what this survey data may mean specifically in terms of the creation and utilization of a Trust-Commitment culture. To aid the reader in avoiding confusion about the stages of data analysis, it may be helpful to put a "name tag" on each of the stages: Stage I - Managerial Style; Stage II - Managerial Essentials; Stage III - Managerial Culture. Before getting deeply into the survey data diagnosis, it may be helpful to give some background on the history and theory of 1) employee survey assessment in general, and 2) the Quality Leadership Survey in particular. The 18 businesses are briefly described. Also given are some of the statistical highlights of the survey responses by the 1,000 plus employees. All of this leads to a discussion of how a Trust-Commitment Managerial-Culture Model should be considered the cultural centerpiece of the way successful women entrepreneurs operate their businesses and how this may be significant information to use in the training and development of future women entrepreneurs.

The History and Theory of Employee Survey Assessment

Surveys being used in the development of work groups and organizations began in the 1930s (Likert, 1932). Likert was a pioneer in the survey guided organizational improvement effort forming the Institute for Social Research (ISR) in 1947 at the University of Michigan . The well-regarded Survey of Organizations (SOO) (Taylor & Bowers, 1972) was developed by ISR in the 1960s. This "grandfather" of employee organizational assessment surveys put to work Likert's and other Institute researchers' four factor theory of leadership along with Likert's Socio-Technical and Linking Pin organizational functioning theory (Likert, 1961,1967). Employee organizational surveys have several purposes according to a number of researchers: pinpointing areas of concern, identifying long-term trends, monitoring program impact, and aiding communication. To some of these survey experts, the main purpose of these surveys is assessment and improvement (Kraut, 1996; Nadler, 1996; Taylor & Bowers, 1972). The Center for Effective Organizations at the University of Southern California has been tracking for a number of years how employee surveys have been helping major corporations achieve higher performance. The Center noted in the decade of the 1990s how the employee survey, when combined with TQM and other employee involvement programs, resulted, as viewed by employees, in considerably increased employee and customer satisfaction, productivity, and profitability (Lawler, Mohrman, & Ledford, 1992, 1995, 1998). Burke and others have proposed models for helping organizations better their performance through formal change programs involving employee surveys (Burke, 1994; Burke, Coruzzi, & Church, 1996; Burke & Litwin, 1992).

The Quality Leadership Survey (QLS) was designed in the early 1990s to assist a major military health care facility in its transitioning to a Quality system and method. This large medical organization wanted an inexpensive and efficient means of assessing and tracking its Quality improvement efforts over a multi-year period. The QLS was modeled after the Institute for Social Research's Survey of Organizations (SOO) in that it seeks employee views of broad organizational dimensions (Culture, Policy, Managerial Leadership, Peer Leadership, and Social Outputs) by using a multi-question index format to isolate 32 key variables/factors (such as communication and teamwork) that reflect these dimensions and influence organizational performance. The theoretical framework of the QLS incorporates Likert's views of how organizations function and adds Quality principles and methodology. Since its inception, the QLS has been used in a number of organizations from a variety of industries. The Guidebook for the Quality Leadership Survey was written to provide definitions, examples, explanations, and the processes for its effective administration, feedback, and long term utilization. There are also sections dealing with the development and the theory of the survey ( Davis , 1993).

The foundation of the QLS resides with the measurement of an organization's culture. It is the first of the five dimensions making up the survey with the other four following in the order of Policy, Managerial Leadership, Peer Leadership, and Social Outputs. The Culture dimension is composed of seven factors indexed by 21 questions, three questions per factor: Mission/Vision, Innovation, Involvement, Learning, Consistency, Improvement, and Ethics. The QLS Culture segment assesses the organization's basic assumptions, beliefs, and values in these seven areas and identifies how the leadership and employees of the organization essentially approach the taking of action to solve daily problems in these vital areas of the functioning of the organization (Schein, 1987). The natures of these factors are critically important to the formation of the factors in the follow-on dimensions. In other words, the Culture factors impact the other dimensions' factors one after the other in a cascading manner (Culture factors impact Policy factors, Policy factors impact Managerial Leadership factors, etc.).

Several writers have pointed out the significance of culture to organizational performance. Schein sees culture as the values/beliefs/assumptions system used by the leadership and membership of an organization, which determines how the organization reacts to both crucial internal and external forces. He states culture is the single most important area of responsibility for senior managers (Schein, 1987). In the mid-1980s, Dennison, after studying more than 300 U.S. companies concluded, the company with a participative culture had twice the profitability of one with a non-participative culture ( Denison , 1984). Then, Kotter and Heskett in the early 1990s released extensive data of their 11 year study concerning more than 200 blue chip American companies, showing those with healthy adaptive and caring cultures had a much greater profit and stock price appreciation than those having unhealthy non-adaptive and non-caring cultures.

Looking at the other four QLS dimensions, the Policy dimension also has seven factors (Systemizing, Communication Flow, Team Problem Solving, Sensitivity, Bottom-Up Influence, Knowledge , and Teamwork). They measure the senior managers' guidelines, procedures, and practices in these seven key operating categories of the organization, which once again impact how managers and employees solve problems and take action on a daily basis.

Falling under the dimension of Managerial Leadership are seven critical kinds of behaviors and actions of an organization's middle and lower managers and its super-visors. These are Self Worth, Teamwork, Team Goals, Team Problem Solving, Participation, Learning, and Technical/Interpersonal Skills.

The Peer Leadership dimension and factors are the same as those found in Mana-gerial Leadership. The difference between the two is employees are asked how they see themselves as a team performing on these seven crucial behaviors and actions rather than how they see their formal managers and supervisors performing on these factors.

The last of the five dimensions is Social Outputs. It deals with organizational non-financial outcomes. With these factors, employees assess what has been the results over the past twelve months of how work has been organized (Systemizing of Work), how much team effort has taken place (Team Effort), how much individual and group satisfaction has occurred (Individual/Group Satisfaction), and to what extent trust and commitment have existed within the organization (Trust/Commitment). There are four questions which deal with the Trust-Commitment factor that is at the heart of this paper. They play a significant part in the statistical assessment of the survey results presented later in the paper. They are given here as they appear in the QLS: To What Extent

92. Is there an environment of trust and trustworthiness throughout the

organization?

93. Is the organization dedicated to following a set of rules and practices

which ensure a sense of "fair play" and honesty among all stakeholders,

especially employees?

94. Are you committed to the organization, its mission , and objectives?

95. Is the organization committed to you, your goals, and welfare?

A more complete understanding of the construction of the QLS and why the initial seven factors in the Culture dimension were chosen to drive the survey can be found by referring to the research of the authorities in each of the seven factor areas: Culture (Kotter & Heskett, 1992; Schein, 1987), Mission/Vision (Deming, 1986, 1993); Innovation (Drucker, 1985); Involvement (Denison, 1990; Likert, 1967); Learning (Senge, 1994); Consistency (Deming,1986; Denison, 1990); Improvement (Deming, 1986); and Ethics (Covey, 1992). Keep in mind the overall aim of the QLS is to aid an organization in a long-term and difficult improvement effort to achieve a Quality philosophy supported by Quality systems, methods, processes, and practices. It is expected several annual administrations of the survey over a multi-year period with extensive feedback and action-taking on the part of both management and employees is necessary in order to move an organization from a non-Quality condition to that of a predominantly Quality way of operating.

The Business and the Beginning of Survey Data Analysis

The full details of the continuing research of successful women businesses using the QLS (including the sampling and research method, as well as extensive statistical findings) can be found in a recent article ( Davis , 2005a). The surveying at the women-owned businesses was completed in 2000, while the surveying of the men-owned businesses had been done in the mid-1990s. There was similarity between the businesses of the two categories of owners. The female group of business owners was involved in 12 different types of businesses, and those in the male group had a female counterpart in terms of types of businesses. All had been in existence for at least ten years. The range of number of employees was 22 to 367 (women) and 15 to 310 (men). The average number of employees was 115 to 138, respectively. The average annual sales for the women owned firms were $28 million, which were approximately twice the average annual sales of the men owned companies. The female firms came from all regions of the U.S. , but unlike them, the male-owned companies came from a single region of the country. Employee survey participation was 31% for the women-owned firms (507 of 1,612) and 90% for the men (499 out of 552). Both hourly and managerial, female and male employees from the two groups of ownership responded to the survey (Davis & Hollingsworth, 2000).

. Starting out (Stage I of the data analysis), the main purpose of the examination of the 14 highly successful women-owned firms with the QLS in 1999 and 2000 was to identify their level of functioning in the 32 categories of the QLS. The comparison with the four men-owned companies allowed a gender difference to be considered in the inquiry. Likert held the view organizations having a participative and consultative approach to leading and managing would be higher performing than those with auto-cratic/authoritarian and bureaucratic styles (Likert, 1967). Thus, the 1999-2000 study in the beginning had the dual hypotheses the women owners would

1) Lead and manage in a participative and consultative manner and

2) Score higher on the 32 factors of the QLS because they had much higher annual revenues.

These hypotheses were accepted with one minor qualification (Davis & Hollingsworth, 2000). Note that when this 1999-2000 study was begun, the pinpointing of a specific kind or type of culture was not the original intention in surveying the 18 businesses involved in the study.

The early analysis of the survey results were examined in more detail as to what it is about the participative/consultative leadership styles that might cause the highly suc-cessful woman entrepreneur to be able to achieve such outstanding results. A broad statistical analysis on three fronts (reliability - Cronbach Alpha; validity - Discriminant Pearson Product Moment; and factorial extraction - Principal Components) was employed to discover these key leadership and management activities.

The Survey Data, Findings, and Early Conclusions

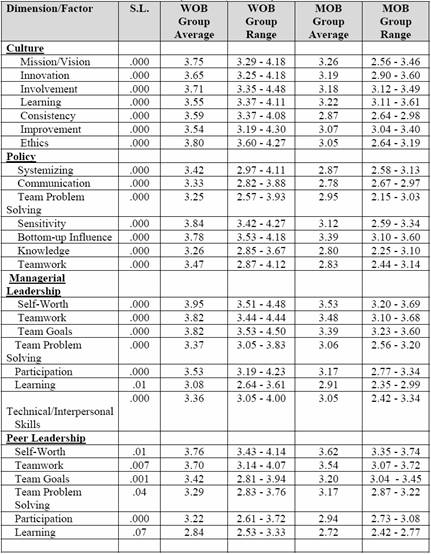

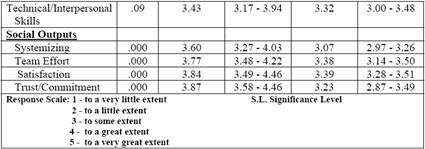

Table I presents the data for the two groups on the 32 QLS factors, which of course includes those of the Culture and Social Output dimensions. A five point Likert scoring scale is used in the answer format of the QLS. An overall average for the women-owned businesses (WOB) and the men-owned (MOB) on each of these factors are shown. The low and high scoring companies for the two groups are also given in the table by factor. It may be interesting to note the overall averages for the WOB were significantly higher to at least the .05 level (t-test analysis of significance of difference using SPSS software) for 30 of the 32 QLS factors, including all of those in the Culture and Social Output. It was found in the 1999-2000 study that the WOB had cultures, policies, managerial actions , and peer leadership which were quite high on the five point QLS measurement scale; were more participative/consultative in their general leadership approach compared to the MOB; and produced more favorable social outcomes than the MOB (Davis & Hollingsworth, 2000).

As mentioned earlier, the QLS data from the 1999-2000 study was examined statistically to determine the reliability, validity, and factorial characteristics of the survey following the approach the Institute for Social Research used to establish the reliability and validity for its Survey of Organizations (Taylor & Bowers, 1972). Using SPSS software, Cronbach Alpha reliability coefficients came to .9647 for the 32 factors and .9800 for the 95 questions.

SPSS Discriminant Validity computations for the 32 factors and the 95 questions were also done. Rather than provide the Pearson Product Moment correlations for every factor with all of the remaining 31 factors--for the purpose of this paper and the sake of brevity--what is presented here are those relevant to the factors found within and between the Culture and Social Output dimensions. The correlations for the Culture factors (the seven compared to each other) had a range of .46 for the low and a high of .70, while the average was .57. The correlations for the four factors inside the Social Output dimension were .55 (low), .67 (average), and .78 (high). The correlations between the seven Culture factors and the four from Social Output came out to .34, .50, and .69 for the low-average-high correlations. After a close examination of the entire matrix of factor correlations, the conclusion was drawn that the QLS is generally characterized by strong discriminant validity across all its dimensions and factors. A correlation matrix was also completed for the 95 questions so discriminate validity could be analyzed question by question.

Thirdly, a principal components SPSS factorial analysis of the questions, factors, and dimensions was performed (Harman, 1976). For the questions, 13 of them had eigen-values greater than one; for the factors, four; and for the dimensions, only one. This perplexing outcome led to a closer study of what were the forces really at work inside these highly successful women led and owned firms. Stage II of the data analysis was launched as a result.

To make sense out of the statistics, the 95 question factorial analysis was scrutinized to identify the 13 questions which had the greatest number of correlation matches to at least the .50 level. These questions were then separated into four groups, each group seeking a common theme. Upon this closer review, the questions were isolated into four specific Successful Entrepreneurial Leadership essential characteristics: 1) Team Oriented; 2) Ethical; 3) Developing the Knowledge and Skills of Its Employees; and 4) Trusted By and Committed to Its Employees.

This left the discovery of an explanation for the one component with an eigen-value greater than one that was found in the five dimension factorial analysis. The Institute for Social Research provides a multi-faceted answer to this statistical question. The Institute has found in trying to pinpoint the more precise composition of the four indices that make up the Survey of Organization's Supervisory Leadership dimension (Support, Goal Emphasis, Work Facilitation, and Interaction Facilitation) that there is a general factor that makes up between 39 to 45% of each of these indices. In each instance, this is a majority of the explanation of the variance for any of the four indices. The Institute states that there are probably at least four contributors to a general leadership factor: 1) "factorial impurity" in any leadership item (i.e. each item assesses more than one leadership factor); 2) each leadership factor is assessed by the same method or survey with the same respondents at the same time; 3) a general "halo" effect, which causes a respondent to view a manager in altogether positive or negative terms; and 4) a "real world" relationship with leadership behavior in which good things tend to be seen going together (Taylor & Bowers, 1972). At this time of Stage II analysis, the conjecture was made that this general leadership factor could be operating in the QLS because it employs different dimensions than the Survey of Organizations (SOO) and because it may be seen as more abstract in nature with the dimension of Culture. This greater degree of abstractness in the QLS could result in this general factor operating as much or more in it as within the SOO. Identified at this time was the plausible idea that the single force operating inside surveys such as the QLS or SOO could be a "Leadership Security" factor in which employees have a comfort level or a "secure" feeling that they know their leaders will do the right things to cause their organization to not only survive but to succeed. "Leadership Insecurity" could exist as well in organizations not well lead or managed. Also brought forward in embryonic form was the idea that this single or general factor could be a specific kind or type of "culture" for these women owned businesses.

Further Reflections on the Data and Findings

A period of time has passed since the last reporting of the data presented in Table I and its analysis ( Davis , 2005a). This chance for greater reflection has allowed the authors to give deeper consideration to what these data possibly mean in terms of culture, not just the kind of managerial style or the essence of what that management approach should be, particularly when thinking about the training and development of new women entrepreneurs. There has been no change to the general suggestion that prospective women entrepreneurs seriously consider adopting a participative/consulting, team-oriented, and ethical management system that strongly trains and develops the firm's employees. Rather, the modification to what has been previously proposed is in the idea that the woman entrepreneur starting out or one wanting to expand or improve her going concern be very conscious of the core responsibility to initiate and foster a "culture of trust and commitment." It is believed that this trust-commitment culture that achieves the strongest of bonds between employees and their small business employer and the highest levels of performance is established and furthered by the owner showing from the beginning an unwavering and unquestioned trust and commitment to her employees.

To support this position, the authors offer three categories of statistical data. First, there is the factorial analysis of only one dimension having an eigen-value of one. The theory behind the structure of the QLS is that Culture is the prime consideration of the five dimensions ( Davis , 1993). It makes sense to the authors that Culture factors shape Policy factors, Policy factors shape Managerial factors, and on down the cascade. The next category of statistical data adds weight to Culture being the prime dimension. Examine the highest scoring factors for the WOB (at or above 3.75) in Table I going from Culture down to Social Outputs: Mission/Vision (3.75); Ethics (3.80); Sensitivity to Customers and Employees (3.84); Bottom-Up Influence (3.78); Building the Employees' Sense of Self Worth - Managerial Leadership (3.95); Teamwork - Managerial Leadership (3.82); Team Goal Setting - Managerial Leadership (3.82); Building the Employees' Sense of Self Worth - Peer Leadership (3.76); Team Effort (3.77); Individual/Group Satisfaction (3.84); and Trust/Commitment (3.87). With the arrangement of the above high scoring survey results, the authors believe successful women entrepreneurs create a values/beliefs/assumptions system founded on trust and commitment when they 1)have a mission/vision that is ethics driven, which then 2) creates policies (written or unwritten) that encourage sensitivity to employees' and customers' needs and that seeks to listen to the lowest level employee, then 3) builds the sense of self worth of employees while emphasizing teamwork and team goal setting, which then 4) gets employees to build each others sense of self worth, and then 5) results in an overall environment of high individual and group satisfaction, team effort, and trust and commitment. With this sequence, it seems a proper order and logic has been followed in concluding that high trust and commitment starts with a culture that is mission/vision/ethics driven.

Lastly, other new statistics are presented at this point in an effort to affirm this idea of a Trust/Commitment culture existing in these women's firms. Reported now is previously unpublished data from the surveying of the more than 1,000 employees concerning the four questions which make up the Trust/Commitment factor in the Social Output dimension of the QLS. Question 92 asks about the extent of an environment of trust and trustworthiness in the company. Question 93 asks about a set of rules/practices ensuring fair play and honesty especially among employees. Question 94 asks about the employee being committed to the company and its mission/objectives. Question 95 asks about the company being committed to the employee. The Pearson Product Moment correlations among these questions are

Question 92 (Trust) with 93 (Ethics) is .73;

Question 92 (Trust) with 94 (Employee Commitment to Company) is .47;

Question 92 (Trust) with 95 (Company Commitment to Employee) is .64;

Question 93 (Ethics) with 94 (Employee Commitment to Company) is .48;

Question 93 (Ethics) with 95 (Company Commitment to Employee) is .64;

Question 94 (Employee Commitment to Company) with 95 (Company Commitment toEmployee) is .58.

Although there is no valid and genuine way of determining true cause and effect among these correlations and whether a larger correlation is more meaningful, it is feasible in the view of the authors to think that ethical actions by the company builds trust with employees (.73), trust comes with the company's commitment to the employee (.64), company commitment to the employee comes before employee commitment to the company (.64 compared to .48), and that employee commitment to the company comes with company commitment to the employee (.58). This arrangement of the correlation outcomes with these four questions concerning the Trust-Commitment small business company culture suggests that once the owner demonstrates an unquestioned trust and commitment to employees, then the trust and commitment by employees is reciprocated. We believe this data offers new insights into how trust and commitment is initiated and established in the firms of successful women entrepreneurs.

After all this QLS data study and analysis, it is suggested that a Trust-Commitment Model, which is an amalgamation of what has been found separately by writers such as Ciancutti and Steding and the SPEC researchers, may be a key aspect to the success of the group of highly successful women business owners studied. What may have been done in using the QLS survey with these 18 businesses is to tease out the distinct manner in which a Trust-Commitment Management Culture Model originates and operates. As a result of this further extensive statistical analysis of the QLS survey results of these businesses, we now propose the hypothesis that these women's management style has been one in which they have emphasized the training and development of their employees, been highly ethical in all their dealings with both employees and customers, and extensively utilized teamwork in order to create a "culture of trust and commitment." After considerable review of the survey data, the authors believe when an employee is well trained in the job, is treated fairly and ethically on a daily basis, views all employees in the firm as cooperating and collaborating to make the business a success, and is trusted by and is committed to by the owner, the employee (along with other employees similarly treated) will trust the employer and be committed to high individual and organizational performance. The writers of this paper believe it is reasonable to draw this conclusion and encourage other researchers to study the hypothesis proposed here.

Other researchers are needed to conduct additional studies of the trust-commitment cultural model, to expand the samples of both the number of employees and the number of firms involved. Further use of the QLS in additional research projects of this kind will add to the theory, reliability , and validity of this employee organizational assessment instrument. This study has explored new ground and provides initial statistical evidence that highly successful women entrepreneurs fundamentally lead and operate their businesses in a team oriented, ethical, and knowledge/skills building and trust/commitment building way that produces not only very good financial results, but also favorable social organizational outcomes. It appears these women develop and utilize a distinct type of culture when compared to a sample of male entrepreneurs. The information presented here, if corroborated by future studies, may assist in improving the future career guidance, education, training , and the mentoring of the large number of women who will aspire to become business owners in the U.S. this decade.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper has not been to establish any finality as to how women should operate their businesses in the future, but to encourage much more extensive research into the question of how millions of women might pattern themselves after already well established, proven, and highly successful women business owners. The writers would like to suggest that for employee survey assessment research of women owned businesses, a design found in the Guidebook for the Quality Leadership Survey (Davis, 1993) be used. The design is very much in keeping with the Deming-Shewart Plan-Do-Study-Act action research model and involves the annual administration of the QLS to the employees of a business over a three or four multi-year period. In a way, the training and development of entrepreneurs in this manner might be described as "action research training and development." With each administration of the survey and the feedback of survey results, the managers and employees are able to identify high priority improvement categories and to take action. The follow up surveying enables the owner/ manager and the organization to learn if the action taking achieved the desired results for improved organizational performance from both financial and social perspectives. This research/training and development pattern provides managers and employees a systematic way to deal with the complex evolution of their company while it is conducting its daily business in a competitive and changing environment. With this additional research, not only can small business organizational culture theory be advanced, but the success of new entrepreneurs can be furthered as well.

TABLE I - QLS COMPARISON DATA, 18 COMPANIES (WOB-14; MOB -4)

References

Baron, J. N., & Kreps, D. M. (1999). Strategic human resources: Frameworks for general managers. New York : Wiley & Sons.

Becker, T. E., Billings , R. S., Eveleth, D. M., & Gilbert, N. L. (1996). Foci and bases of employee commitment: Implications for job performance. Academy of Management Journal , 39 (2), 464-483.

Beyerlein, M. M., Freedman, S., McGee, C., & Moran, L. (2003). The ten principles of collaborative organizations. Journal of Organizational Excellence , 22 , 51-64.

Brooks, A., & Zeitz, G. (1999). The effects of total quality management and perceived justice on organizational commitment of hospital nursing staff. Journal of Quality Management , 4 , 69-94.

Burke, W. W. (1994). Organization development: A process of learning and changing . Reading , MA : Addison-Wesley.

Burke, W. W., Coruzzi, C. A., & Church, A. H. (1996). The organizational survey as an intervention for change. In A. I. Kraut (Ed.), Organizational surveys (pp. 41-66). San Francisco : Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Burke, W. W., & Litwin, G. H. (1992). A causal model of organizational performance and change. Journal of Management , 18 , 523-545.

Ciancutti, A., & Steding, T. L. (2001). Built on trust . Chicago : Contemporary Books.

Costigan, R. D., & Iter, S. S. (1998). A multi-dimensional study of trust in organizations.

Journal of Managerial Issues , 10 , 303-318.

Covey, S. R. (1992). Principle-centered leadership . New York : Summit Books.

Davis, J. J. (1993). Guidebook for the quality leadership survey . San Antonio , TX : STAR Quality.

Davis, J. J. (2001). The succeeding personalities of women entrepreneurs . San Antonio , TX : STAR Quality.

Davis, J. J. (2005a). The new role of employee survey assessment in the development of quality women owned businesses. The Journal of Leadership Research , 2 .

Davis, J. J. (2005b). The team oriented personality and leadership of highly successful women entrepreneurs. The Journal of Leadership Research , 2.

Davis, J. J., & Hollingsworth, R. H. (2000). An exploration of the leadership effectiveness of highly successful women entrepreneurs. Business Journal for Entrepreneurs , 24 , 32-46.

De Gilder, D. (2003). Commitment, trust and work behavior: The case of contingent workers. Personnel Review , 32 , 588-605.

Deming, W. E. (1986). Out of the crisis . Cambridge , MA : MIT.

Deming, W. E. (1993). The new economics for industry, government, and education . Cambridge , MA : MIT.

Denison , D. R. (1984). Bringing corporate culture to the bottom line. Organizational Dynamics , 13 , 5-22

Denison , D. R. (1990). Corporate culture and organizational effectiveness . New York : Irwin.

Dietz, G. (2004). Partnerships and the development of trust in British workplaces.

Human Resource Management Journal , 14 , 5-25.

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2000). The effects of trust in leadership on employee performance, behavior, and attitudes: A meta-analysis. In S. J. Havlovic (Ed.), Academy of Management Best Paper Proceedings , OB : H1

Drucker, P. F. (1985). Innovation and entrepreneurship . New York : Harper & Row.

Foote, D. A., Seipel, S. J., Johnson, N. B., & Duffy, M. K. (2005). Employee commitment and organizational policies. Management Decision , 43 , 203-220.

Gibb, J. R. (1978). Trust: A new view of personal and organizational development . Los Angeles : The Guild of Tutors Press.

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis . Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

Kim, J. W., & Rowley, C. (2005). Employee commitment: A review of the background, determinants and theoretical perspectives. Asia Pacific Business Review , 11 , 105-125.

Kotter, J. P., & Heskett, J. L. (1992). Corporate culture and performance . New York : The Free Press.

Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology , 50 , 569-597.

Kramer, R. M., & Tyler, T. R. (Eds.). (1996). Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research . Thousand Oaks , CA : Sage Publications.

Kraut, A. I. (1996). Introduction: An overview of surveys. In A. I. Kraut (Ed.), Organizational surveys (pp. 1-14). San Francisco : Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Lane, C., & Bachmann, R. (Eds.). (2003). Trust within and between organizations : Conceptual issues and empirical applications . New York : Oxford Press.

Lawler, E. E., Mohrman, S. A., & Ledford, G. E. (1992). Employee involvement and total quality management . San Francisco : Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Lawler, E. E., Mohrman, S. A., & Ledford, G. E. (1995). Creating high performance organizations . San Francisco : Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Lawler, E. E., Mohrman, S. A., & Ledford, G. E. (1998). Strategies for high performance organizations . San Francisco : Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology , 140 , 1-55.

Likert, R. (1961). New patterns of management . New York : McGraw-Hill.

Likert, R. (1967). The human organization . New York : McGraw-Hill.

McCauley, D. P., & Kuhnert, K. W. (1992). A theoretical review and empirical investigation of employee trust in management. Public Administration Quarterly, 16 , 265-286.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace . Thousand Oaks , CA : Sage.

Nadler, D. A. (1996). Setting expectations and reporting results. In A. I. Kraut (Ed.), Organizational surveys (pp. 177-203). San Francisco : Jossey-Bass Publishers.

O'Brien, R. C. (2001). Trust: Releasing the energy to succeed. New York : Wiley & Sons.

Office of Advocacy: The Voice for Small Business in the Federal Government and the Source for Small Business Statistics. (2005). Retrieved October 3, 2005, from www.sba.gov/advo (2005).

Ramo, H. (2004). Moments of trust: Temporal and spatial factors of trust organizations. Journal of Managerial Psychology , 19 , 760-776.

Schein, E. H. (1987). Organizational culture and leadership . San Francisco : Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Senge, P. M. (1994). The fifth discipline . New York : Doubleday Currency.

Stanford Project on Emerging Companies. (2004). Retrieved October 3, 2005, from, www.gsb.stanford.edu

Taylor, J. C., & Bowers, D. G. (1972). Survey of organizations . Ann Arbor , MI : Institute for Social Research.

Tyler, T. R. (2003). Trust within organizations. Personnel Review , 32 , 556-569.